|

12 January 2010

A Cochrane review found that current evidence does not support the use of combination therapy with ICS plus LABA as first choice preventer therapy in adults and children with persistent asthma, without a prior trial of ICS alone.

Level of evidence:

Level 1 (good quality patient-oriented evidence) according to the SORT criteria.

Action

Health professionals should follow the BTS/SIGN guideline on the management of asthma. For patients not adequately controlled on a short-acting beta2-agonist when required (step 1), inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) are the first choice regular preventer therapy (step 2). Current evidence does not support using combination therapy with an ICS plus a long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA) as first choice preventer therapy, without a prior trial of ICSs alone.

What is the background to this?

The British asthma guideline, published jointly by BTS and SIGN, advocates a stepwise approach for the treatment of adults and children with asthma. ICSs are the first choice regular preventer therapy for adults and children for achieving overall treatment goals. They should be considered for patients with any of the following asthma-related features:

- one or more exacerbations of asthma requiring oral corticosteroids in the last two years

- using inhaled beta2-agonists three times a week or more

- symptomatic three times a week or more

- waking at least one night a week

A proportion of patients with asthma may not be adequately controlled on an ICS alone at step 2. For adults and children aged 5 to 12 years, the addition of a LABA (salmeterol or formoterol) to an ICS should be considered (step 3). For children under five years, the first choice add-on therapy to an ICS is a leukotriene receptor antagonist. However, before adding or changing treatment practitioners should check compliance with existing therapy, check the patient’s inhaler technique and eliminate trigger factors.

As we discussed in a MeReC Bulletin on asthma, a small but significant increase in serious adverse events and asthma mortality has been observed with LABAs in some meta-analyses. This appears to be substantially reduced, but perhaps not abolished when LABAs are used concurrently with an ICS. Monotherapy with salmeterol or formoterol alone has been associated with significant adverse events, and therefore LABAs should only be used in conjunction with an ICS (step 3). To ensure safe use, the Commission on Human Medicines (CHM) has advised that for the management of chronic asthma, LABAs should:

- be added only if regular use of standard-dose ICSs has failed to control asthma adequately

- not be initiated in patients with rapidly deteriorating asthma

- be introduced at a low dose and the effect properly monitored before considering dose increase

- be discontinued in the absence of benefit

- be reviewed as clinically appropriate: stepping down therapy should be considered when good long-term asthma control has been achieved.

Despite current guideline recommendations, data from observational studies indicate that the introduction of LABAs in mild asthma is still common in adults and children, without a prior trial of ICS alone. Therefore, the aim of this Cochrane review was to examine the safety and efficacy of initiating a combination of ICS plus LABA in adults and children with persistent asthma, who had not been previously treated with ICSs.

What does this study claim?

This review of 28 comparisons from 27 RCTs (n=8,050) claims that current evidence does not support the use of combination therapy with ICS plus LABA as first line treatment in adults and children with asthma, without a prior trial of ICSs. In steroid-naïve patients with mild to moderate airway obstruction, the combination of ICS plus LABA was not associated with a significantly lower risk of patients with exacerbations requiring oral corticosteroids (relative risk [RR] 1.04, 95%CI 0.73 to 1.47, P=0.83) or requiring hospital admissions (RR 0.38, 95%CI 0.09 to 1.65), compared to a similar dose of ICS alone. However, ICS plus LABA significantly improved lung function, reduced symptoms and marginally decreased rescue beta2-agonist use. There were no statistically significant differences in the risk of adverse events and withdrawals, although there was a four-fold increase in tremor in the combination group.

Compared with increasing the dose of ICS by 200 to 300microg/day, adding a LABA to the ICS was associated with an increased risk of exacerbations requiring oral corticosteroids (RR 1.24, 95%CI 1.00 to 1.53, P=0.05), although this was at the limit of conventional levels of statistical significance. The combination of ICS plus LABA was also associated with a significantly higher risk of study withdrawals (RR 1.31, 95%CI 1.07 to 1.59). There was no statistically significant group difference in the risk of serious adverse events.

So what?

This systematic review supports the BTS/SIGN asthma guideline’s stepwise approach to the management of asthma. However, many health professionals initiate combination therapy with ICS plus LABA in patients with asthma, without a prior trial of ICS alone.

This review found that in steroid-naïve patients with persistent asthma, ICS plus LABA did not significantly reduce exacerbations requiring oral corticosteroids, compared with ICS alone. The non-superiority of ICS plus LABA over ICS alone in these patients may seem surprising. There may be a perception of greater efficacy of combination ICS plus LABA, given that the addition of a LABA to patients already taking an ICS (i.e. step 3) can lead to improvements in lung function, symptoms and decreased exacerbations.

The authors of this Cochrane review comment that the impact of adding a LABA needs to be assessed separately in these different populations. The apparent divergence in response to a LABA between steroid-naïve patients and patients who remain poorly controlled while on ICS, suggests that, in steroid-naive patients, asthma control is achieved in the majority of patients with ICS alone. In addition, only a negligible reduction was seen in the need for rescue beta2-agonists with ICS plus LABA (on average, one puff fewer every 2-3 days), compared with a similar dose of ICS alone.

The authors did observe a greater improvement in lung function and symptoms, and minimal reduction in the use of rescue beta2-agonists with combination ICS plus LABA, compared with similar doses of ICS alone. However, most studies were relatively short duration (12 weeks or less), and therefore long-term studies in steroid naïve patients are needed.

BTS/SIGN recommend that the addition of a LABA to an ICS should be treated as a therapeutic trial. If there is no response to treatment, the LABA should be discontinued, or if there has been partial benefit, the LABA should be continued, and the dose of ICS increased (up to 800 micrograms/day for adults, 400 micrograms/day for childrena). If a combination of ICS plus LABA is initiated prior to ICS alone, it is impossible to titrate treatments to individual patient response. Consequently, previously steroid-naïve patients may potentially be taking a LABA that is ineffective, but will still be subject to possible adverse effects.

Furthermore, the CHM recommends that for the management of chronic asthma, LABAs should only be added if regular use of standard-dose ICSs has failed to control asthma adequately. Patients should report any deterioration in symptoms following initiation of treatment with a LABA. Any adverse reactions that are thought to occur as a result of treatment for asthma should be reported to the MHRA through the Yellow Card Scheme.

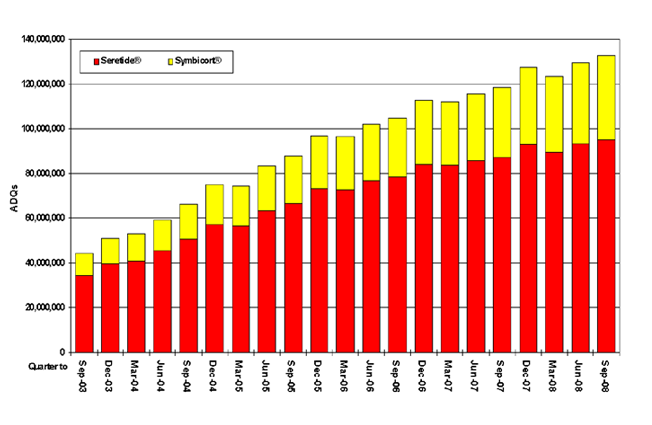

Figure 1. Trends in usage of Seretide® and Symbicort® in General Practice In England (Quarter to Sept 03 – Sept 09)

Click on the graph to enlarge

© NHSBSA 2009

Figure 1 shows the increase in prescribing of ICS/LABA combination inhalers in England from July 2003 to September 2009. A significant proportion, but by no means all of this prescribing will be for patients with COPD, but it would appear that increasing numbers of patients with asthma are being treated at BTS/SIGN step 3 or above. This apparent increase in ICS/LABA prescribing may reflect better treatment for previously under-treated patients. Alternatively, it may reflect patients being stepped up from step 2 to achieve control of their asthma, but not being stepped back down again, or steroid-naïve patients being treated with ICS/LABA, and missing step 2 out completely. In either case, this would seem to represent inappropriate management of these patients. BTS/SIGN guidance recommends stepping down therapy once asthma is controlled, but this recommendation appears to be sub-optimally implemented, leaving some patients over-treated.

Finally, although this review found that children appeared to respond similarly to adults, given the small number of children contributing data, no firm conclusions could be drawn regarding combination therapy in steroid-naïve children. Given the lack of data here, and the CHM advice on LABAs, current BTS/SIGN recommendations for children should be followed. As with adults, evidence does not support the use of ICS plus LABA in children with asthma, without a prior trial of ICS.

aBeclometasone equivalent doses.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis of 28 comparisons drawn from 27 RCTs (23 adult, 5 children).

Patients

8,050 adults and/or children aged two years and above with persistent asthma of any severity who had not received ICSs in the month preceding enrollment. Baseline data showed moderate or mild airway obstruction (FEV1 >65% predicted). All participants had inadequate asthma control prior to enrollment, with ongoing symptoms and use of rescue short-acting beta2-agonists. Participants were also naïve to LABAs.

Intervention and comparison

There were two comparisons:

1. ICS plus LABA compared with a similar dose of ICS (24 studies)

2. ICS plus LABA compared with higher dose ICS (4 studies).

Salmeterol was studied in 22 trials, and formoterol in the remaining 6 studies. ICS plus LABA was delivered in a single inhaler in 15 studies, and via two separate inhalers in 13 studies. RCTs of less than 30 days treatment duration were excluded.

Outcomes and results

Primary outcome — patients with exacerbations requiring oral corticosteroids for 5 to 10 days. ICS/LABA was not associated with a significantly lower risk of patients with exacerbations requiring oral corticosteroids compared to similar dose ICS alone (RR 1.04, 95%CI 0.73 to 1.47, P=0.72). Compared to higher dose ICS alone (increasing ICS by 200-300microg/day), there was an increased risk of exacerbations requiring oral corticosteroids (RR 1.24, 95%CI 1.00 to 1.53, P=0.05).

Secondary outcomes — compared to similar dose ICS alone, ICS/LABA was not associated with a significantly lower risk of exacerbations requiring hospital admissions (RR 0.38; 95% CI 0.09 to 1.65), but the combination led to a significantly greater improvement from baseline in FEV1 (0.12 L/sec, 95%CI 0.07 to 0.17), in symptoms (standardised mean difference [SMD] –0.26; 95%CI –0.37 to –0.14) and in rescue beta2-agonist use (–0.41 puffs/day, 95%CI –0.73 to –0.09). There was no significant group difference in the risk of serious adverse events (RR 1.15, 95%CI 0.64 to 2.09), any adverse events (RR 1.02, 95%CI 0.96 to 1.09), study withdrawals (RR 0.95, 95%CI 0.82 to 1.11), or withdrawals due to poor asthma control (RR 0.94, 95%CI 0.63 to 1.41), although there was a significant increase in tremor with ICS/LABA (RR 4.71, 95%CI 1.38 to 16.08).

Compared to higher dose ICS, ICS/LABA was associated with a higher risk of study withdrawal (RR 1.31, 95%CI 1.07 to 1.59). There was no significant difference in most measures of lung function and in the risk of serious adverse events. Due to insufficient data the authors could not aggregate results for hospital admission, symptoms and other outcomes.

Sponsorship

The review was conducted by Cochrane authors. Twenty of the included studies were funded by the manufacturers of LABAs, three studies received funding from a charitable source, and funding was unspecified in the four remaining studies.

More information on the management of asthma can be found on the respiratory section of NPC and in MeReC Bulletin 2008;19(2). The BTS/SIGN asthma guideline was published in May 2008, and has been recently revised.

Feedback

Please comment on this blog in the NPC discussion rooms, or using our feedback form.

Make sure you are signed up to NPC Email updates — the free email alerting system that keeps you up to date with the NPC news and outputs relevant to you